It’s the middle of internet week! I’ve already seen 30+ demos, in addition to Meetup Co-Founder Scott Heiferman smashing an iPad on stage at the tech meetup last night (which was at NYU’ Skirball center). One theme that has been recurrent is that people are unaware of the structure of angel investments. So, I thought I’d give a brief overview of one common structure. Please note there is an excel file you can download at the bottom of the post. It includes detailed notes and may be helpful to have open as you go through the post.

Many seed stage internet businesses look to angels to help them kickstart their companies through growth capital, as well as expertise. It seems that many people are confused as to what a typical angel investment might “cost” them in equity. And, while “a convertible note with a 10% PIK and a 25% discount to the series A” (also known as the “plain vanilla” angel structure) may make sense to some people, I thought I’d break down how to interpret that in case there were any non finance geeks out there who were trying to understand what the terms of an angel investment actually mean.

The Basics

I think it’s easiest to use an example to explain this type of investment. So, Joe is the founder of Newco which is a website that does some sort of location/game based virtual good (insert other buzz words) service. Joe needs to raise $500,000 to hire a few developers and a sales person. Joe finds an angel investor who just happens to have a lot of experience in location/game based virtual good services. Joe’s investor, let’s call her Ms. Jenna, gives him $500,000 and they use the plain vanilla (read typical) angel structure.

Instead of putting a value on the company now, the investor, will get equity based off of the valuation used in Joe’s Series A round of financing (more on that later). Presumably, when Joe raises his Series A, he will have a few customers, some revenues, and a much better picture for how his company will actually operate. His company will therefore be more easily valued.

The PIK

PIK stands for paid in kind. Ms. Jenna is putting up $500,000, and expects Joe to pay her 10% in interest each year. But, Joe doesn’t have any cash as he is a pre-revenue startup. So, instead of paying in cash, Joe is going to take the value of the dollars he would pay Ms. Jenna, and add that to the principal of the investment.

In our example, in the first year, Joe will take the 10% interest payment (worth $500,000 x 10% = $50,000) and add that to the principal of the investment, which will now be $500,000 + $50,000 = $550,000. In the next year, Joe will be charged 10% on that new principal. His new interest payment is $550,000 x 10% = $55,000. And his new principal amount is $550,000 + $55,000 = $605,000. For those familiar, this is the same concept as a negatively amortizing loan. Instead of paying interest in cash, it is paid as principal, which is the same as saying it is paid in kind (PIK).

The Equity Part of the Equation

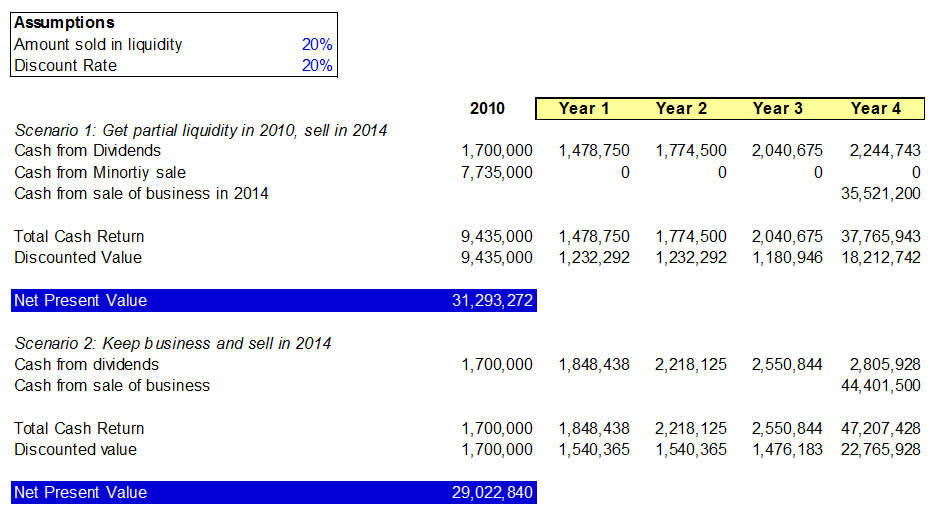

We are going to pretend that Joe had a rough go of it and doesn’t raise his series A for 5 years. In year 5, the principal value of Ms. Jenna’s investment is now $805,225 (please see attached excel to see the calculations, rows 19 and 20 – we just added the 10% interest in each of the 5 years). The series A investor gives Joe $1 million dollars at a $4 million post-money valuation meaning that they will get $1 mm/$4 mm = 25% of Newco’s equity. For the difference in pre vs post money valuations, please see the attached excel cell C14.

We said that the angel investment would be invested at a 25% discount to the series A. This means that instead of investing at a $4 million valuation, Ms. Jenna’s dollars get put to work at a $4,000,000 x (1-25%) = $3 million valuation. And, her $500,000 originally invested has grown to $805,225 due to the interest which has been paid in kind. So, her ownership in the company will be $805,225/$3,000,000 = 27%.

At the risk of complicating things, it is worth noting that Ms. Jenna’s original angel investment can also come with a valuation cap, meaning that there is a maximum value that her dollars can be put to work at. In the excel, I have put this at $10,000,000 so it doesn’t come into play. But, if Joe’s company was worth $20,000,000 in 5 years when he raised his series A, Ms. Jenna’s equity would be calculated using a valuation of $10,000,000, not the typical 25% discount we have used in our example. You can see how this benefits the angel investor in the case that they company does take off. Ms. Jenna will invest her money at a $10,000,000 valuation as opposed to a $ 15,000,000 valuation ($20,000,000 x (1-25%) = $15,000,000) which would give her a larger equity stake in the company.

End Result

Joe has now raised $1.5 million and is hopefully well on his way to a successful career at the helm of Newco. He has given up 25% to his series A investors, and 27% to his angel investor Ms. Jenna, and so retains 48% for himself and the rest of his team.

The attached excel sheet has all of these calculations and is set up in a way that you can play around with different assumptions. Please feel free to email me with any questions! phil (at) philstrazzulla (dot) com. Also, please note that this is meant to be an overview of one type of common angel structure and that there are definitely more out there. Enjoy!

The Excel: Angel Investing Basics