When I worked in venture capital, I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to invest in some really great companies during their early rounds. Now some of those companies are going public, and I find myself spending some time thinking about when to sell my stock in these companies.

I don’t think anyone has truly figured out the formula to value these companies. There just aren’t enough examples of SaaS companies that have reached maturity and shown us what they really look like in the long term. Salesforce still grows at 23% annually and trades at over 100x EBITDA!

Nonetheless, I thought it’d be an honest exercise for me to write some thoughts down and then review them in a few years.

I think that growth should be the number one factor in considering SaaS valuations (when I say valuation, I mean how much is the company worth on a revenue/gross profit/EBITDA/FCF multiple basis). If a company can grow at 50% for 3 years, it’s topline will be nearly 3.4x higher! That’s powerful.

If you’re a real SaaS company, this means you have 80+% gross margins and should start seeing nearly 40 cents/dollar of new revenue start to fall down to operating cash flows. Assuming the company that grows at 50% annually was cash flow breakeven, that means your operating cash flow in three years is more than your current revenues.

No two companies are the same. The top factors that would effect valuation are how scalable growth is (sales/marketing channels and economics), how long growth can go for (market size, competition), churn (and how it contributes to growth), and margin profile (gross and net), barriers to entry (that will protect current revenues and make sure new competition doesn’t chip into existing growth prospects)…there are some other things pretty important too, like management’s incentive system.

I think what a lot of investors have figured out is that if a company keeps growing, you can pay through the nose (relative to what most companies trade at) and still make a nice IRR. I agree that growth is the most important aspect of valuation, and that most of the other factors are basically contributors to growth. Even in these heady times of crazy valuations, I’d say that a lot of the public companies are undervalued! The other main factor here is the margin profile. If you can’t ever be profitable, then forget it. And, in the case SaaS companies, it’s more like you have to be VERY profitable.

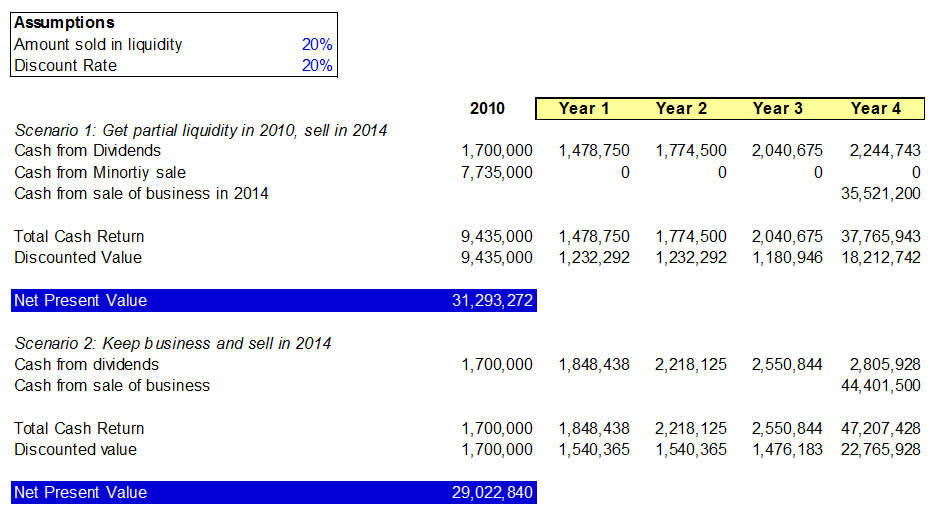

I don’t have time to look up various rules on making stock predictions for companies you own. So, I’ll leave you with this very basic spreadsheet (SaaS valuations thoughts) that should illustrate that growth is key in valuation and how I think various companies should be valued (although I guess the numbers in blue are very much up to interpretation in most companies). Enjoy.